On the evening I went to watch Marc Webb’s The Amazing Spider-Man (2012) with my daughter Pardis, all the cast and crew of The Dark Knight Rises (2012) – reportedly the concluding chapter in Christopher Nolan’s trilogy – had come to our local theatre at AMC Loews Lincoln Square for the premier of the new blockbuster.

On the evening I went to watch Marc Webb’s The Amazing Spider-Man (2012) with my daughter Pardis, all the cast and crew of The Dark Knight Rises (2012) – reportedly the concluding chapter in Christopher Nolan’s trilogy – had come to our local theatre at AMC Loews Lincoln Square for the premier of the new blockbuster.

Tall, heavy set and foreboding men in black were standing between us ordinary folks and the glamorous gathering of leading actors and actresses being escorted up and down the corridors and staircases of the theatre. We saw all the cast of The Dark Knight Rises over the shoulder shot of those men in black and a sea of reporters and photographers.

As we waited for our Spiderman to start, we saw latecomers in their evening dresses, high heels and tuxedos racing to the theatre, after picking up their complementary popcorn. But that night our minds were with a different rodent – the Spiderman not the Batman.

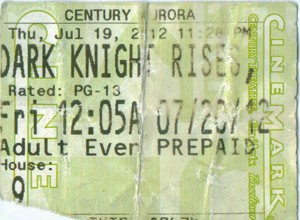

That was Monday evening, July 16, just four nights before the horrific Aurora shooting in Colorado, on July 20, when during a late-night screening, a gunman, James Holmes, allegedly burst into the theatre and started shooting at the audience, killing 12 people and injuring 58 others.

Fact and fantasy of violence

The idea that a person might walk into a movie theatre with weapons and live ammunitions and start shooting at people violates the most sacrosanct assumption about a remissive space in which we enter deliberately to fanaticise – in fact to co-fanaticise together.

A film is just a ruse, an occasion, an excuse, a prop, for the audience to begin to fantasise along the lines offered or suggested by the film they are watching. There are occasionally acts of violence we watch in those remissive spaces, as it is in the Dark Knight Rises. But those are not real violence – they are the simulacrum of violence, they are make-believe. No one gets hurt in those acts. The actors and we along with them just pretend. It’s called acting. We prize the actors who do their acting best, for pretending to do what in fact they are not doing.

But – and here is the rub – fantasising violence, and thus sanitising it of its deadly human costs, is no longer limited to movie theatres as a remissive space or to film as an art form. Self-alienating acts of violence, making them into abstract forms and shapes, are in fact things that modern warfare does best.

War games that simulate real wars for training purposes morph into the video screens of anything, from tanks to fighter jets to submarines (and now to the deadliest of them all pilotless drones), when they are dispatched to kill real people. People who fire at their targets no longer see, with their own naked eyes, the human costs of those fires. All acts of violence become videogames, just like the one President Obama and his close confidants were watching when he ordered the extrajudicial assassination of Osama bin Laden, or when he reportedly prepared his so-called “Kill List”. It is all abstraction and fantasy – just like a movie – with the singular exception that in movies no one gets hurt, not even animals.

The mass murderer who violated the safe sanctuary of that movie theatre in Aurora and started point blank killing people brought criminal fact to that innocent fantasy, live ammunition to that illusory innocence we call cinema.

In that moment, he had joined a fantasy world not too dissimilar to the digitised universe of the person operating a drone from a distance, entirely aloof, indifferent, to the human costs of his actions.

Killing machines

What is a drone – these unmanned, remote controlled killing machines – to which hundreds of innocent civilians in Pakistan and Afghanistan and other places have fallen victim? The technology that makes that digitisation of “the enemy” possible is of the same family genealogy that makes videogame violence, war game panels, and ultimately digital cameras and CGI cinema possible. The nature of contemporary post-modern warfare is the fact that remote control bombing has no moral or physical encounter with the victims it targets. As Al Jazeera reports regarding the drone warfare:

The strategy is giving rise to anxieties that conflict is becoming just a big computer game, in which “desk pilots” in air conditioned bunkers far from the battlefield can kill a few enemy fighters and then go home to their families, remote from the human consequences of their actions or the anguish of associated civilian casualties.

These killing machines have so categorically externalised violence from the conscious metaphysics of the Empire that they are coterminous with dehumanising their enemy, so much so that the term “terrorism” and “terrorist” are now categorically reserved for the Muslims they target – and thus news organisations persistently insist that the murderous act in Aurora had no connection to terrorism. “Authorities have established no terrorism link” – as the BBC so typically puts it, categorically glossing over the terror that people must have experienced in that movie theatre.

The fusion of fact and fantasy in post-modern warfare, the moral depletion of acts of violence from what they mean and what their human costs are in people’s bone and blood are no longer limited to that small theatre in Aurora. It is our global condition – from Gotham and Colorado to Afghanistan and Pakistan.

We can only live by defiance of that fact. With the increased digitisation and privatisation of spectatorship, movie theatres are the very last vestiges of the art and history of cinema as a communal experience, where we can collectively imagine not just what has befallen us as a people, but also to dream our emancipation.

When my daughter Pardis and I saw The Dark Knight Rises in the same theatre a few days later, packed with other New Yorkers, particularly heart warming was to see a young mother, with her baby in a stroller, coming late and looking for a seat in the theatre, just before the silhouette of Bruce Wayne appeared on the big wide screen limping along contemplating his comeback.

Hamid Dabashi is Hagop Kevorkian Professor of Iranian Studies and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, where he teaches social and intellectual history of Iran and Islam, comparative literature, and world cinema.